Foot and Ankle Anatomy: A Quick Reference Map

Your feet carry you through life — literally. Every day, they absorb thousands of pounds of force, navigate uneven terrain, and propel you forward with remarkable precision. Understanding how your feet work can help you recognize when something’s wrong, make better decisions about treatment, and appreciate the incredible engineering beneath you.

Think of your foot as a sophisticated shock absorber, balance system, and launching pad all rolled into one. When everything works together, walking feels effortless. But when even one small part isn’t functioning properly, you’ll definitely notice.

The Architecture: Your Bones

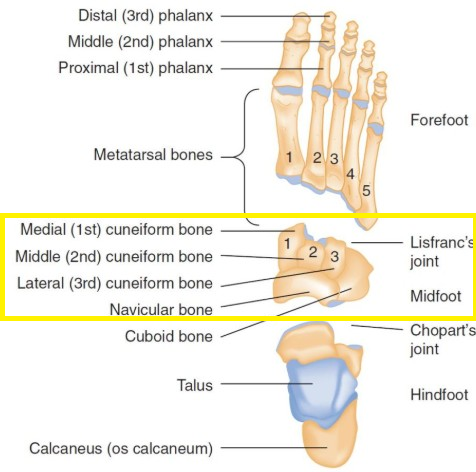

Your foot contains 28 bones working together as an interconnected system (26 main bones plus 2 small sesamoids under your big toe). To make sense of them, picture your foot as a three-story building.

The Foundation (Hindfoot)

Talus and Calcaneus (Heel Bone)

The talus is like the keystone of an arch. It connects your leg to your foot and transfers your body weight downward with each step.

The calcaneus is your heel bone. It’s thick and dense because it strikes the ground first, absorbing impact like a built-in shock absorber.

What this means for you: When heel pain, ankle instability, or arthritis develops, it often traces back to this region.

The Flexible Middle (Midfoot)

Navicular, Cuboid, and Three Cuneiform Bones

These five bones form your arches. They unlock to cushion impact and lock to provide stability when you push off. The navicular on the inside of your foot is especially important for maintaining arch height.

What this means for you: Flatfoot deformity often begins here when the supporting ligaments and tibialis posterior tendon can no longer hold the bones in proper alignment.

The Launch Platform (Forefoot)

Metatarsals and Toes

The metatarsals act like diving boards for each step. The big toe joint is the powerhouse, carrying up to 80% of your body weight during push-off. Underneath it sit two tiny sesamoids that act like ball bearings, reducing friction where tendons glide.

What this means for you: Bunions, big toe arthritis, or sesamoid injuries don’t just cause toe pain — they can change how your entire foot functions.

The Moving Parts: Your Joints

Joints are where bones meet and motion happens. Your foot contains 33 joints, each with a specific role.

Ankle (tibiotalar) joint: Like a gas pedal, it moves your foot up and down for walking, climbing, and running.

Subtalar joint: Located just below the ankle, it tilts your foot inward and outward to adapt on uneven ground.

Midfoot (Chopart and Lisfranc) joints: These joints are your suspension system. They unlock when your foot hits the ground and lock when you push off, creating a rigid lever.

What this means for you: Midfoot injuries, though less common than ankle sprains, can be far more disabling because they disrupt this lock-and-unlock system.

The Support System: Your Ligaments

Ligaments are strong bands of tissue that hold bones together, acting like guy-wires on a tent.

Lateral ankle ligaments (ATFL, CFL, PTFL): These protect against rolling your ankle. The ATFL is the most commonly injured ligament in ankle sprains.

Deltoid ligament: On the inside of the ankle, this is thick and strong. When it tears, it almost always means a major ankle injury.

Spring ligament: This runs under the arch and supports the talus. When it weakens or tears, the arch collapses.

Lisfranc ligament: The keystone of your midfoot. Injury here is often missed but can lead to chronic disability.

What this means for you: Ligament injuries explain why sprains can cause instability and why some patients never feel “right” again without rehab or surgery.

The Powerhouse: Your Muscles and Tendons

Muscles provide the force, tendons are the cables that deliver it.

Achilles tendon: Your strongest tendon, critical for walking, running, and jumping.

Tibialis posterior tendon: Supports the arch. Dysfunction here leads to adult-acquired flatfoot.

Peroneal tendons: On the outside of the ankle, these prevent rolling and stabilize each step.

Small intrinsic muscles: These fine-tune balance and toe alignment. Weakness here can contribute to hammertoes and instability.

What this means for you: Strengthening exercises are not just for athletes. Strong muscles and tendons protect your ligaments and keep your arches healthy.

The Control System: Your Nerves

Nerves both power your muscles and provide sensation.

Tibial nerve: Runs behind the inner ankle. If compressed, you can develop tarsal tunnel syndrome (like carpal tunnel of the foot).

Plantar nerves: Supply most of the sole of the foot and its muscles.

Baxter’s nerve: A small branch often responsible for burning heel pain mistaken for plantar fasciitis.

Peroneal, sural, and saphenous nerves: Control outer and inner foot sensation and some muscles that lift or evert the foot.

What this means for you: Numbness, tingling, or burning pain often signals a nerve issue rather than a simple muscle or bone problem.

The Lifeline: Your Blood Supply

Dorsalis pedis artery: Found on the top of your foot near the big toe tendon — one of the first spots doctors check for circulation.

Posterior tibial artery: Felt behind the inner ankle. Critical for healing wounds on the sole.

What this means for you: Poor circulation makes healing harder, especially in diabetes. That’s why pulses are always checked in clinic.

| Structure | Key Parts | What They Do | Why It Matters to You |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bones | 26 main + 2 sesamoids | Framework for support, balance, push-off | Heel pain, bunions, or flat feet often trace back to bone alignment |

| Joints | Ankle, Subtalar, Midfoot (Chopart/Lisfranc), Toe joints | Create motion and adapt to terrain | Sprains, arthritis, or midfoot injuries affect stability and mobility |

| Ligaments | ATFL, CFL, PTFL, Deltoid, Spring, Lisfranc | Hold bones together, limit excess motion | Sprains and “fallen arches” come from ligament injury or stretching |

| Tendons & Muscles | Achilles, Tibialis Posterior, Peroneals, Intrinsics | Power movement and support arches | Weak or torn tendons cause flatfoot, instability, or toe deformities |

| Nerves | Tibial, Plantar, Baxter’s, Peroneal, Sural, Saphenous | Provide sensation and muscle control | Tingling, burning, or numbness usually means nerve involvement |

| Arteries | Posterior Tibial, Dorsalis Pedis | Deliver blood flow to foot tissues | Poor pulses = poor healing, especially in diabetes |

| Pediatric Notes | Growth plates, Navicular (~3–5 yrs), Calcaneal apophysis | Allow bones to grow and mature | Kids’ X-rays look different; growth plate pain ≠ “just a sprain” |

Special Considerations for Growing Feet

Children’s feet aren’t just smaller versions of adult feet. They develop in stages:

All kids have growth plates — soft areas of cartilage where bone growth occurs.

Flat feet are normal until about age 6 as ligaments tighten and arches form.

Some bones don’t even show up on X-rays until age 3–5 (like the navicular).

The heel growth plate is vulnerable, which is why active kids often get Sever’s disease.

What this means for parents: Don’t panic if X-rays look different from adult films, but don’t ignore persistent pain either. Growth plate injuries are easy to miss and may mimic sprains.

When Things Go Wrong: The Ripple Effect

Your foot is a system. Problems in one area often affect others:

A stiff big toe joint can shift pressure backward, causing heel pain.

Weak hip muscles can increase ankle sprain risk.

Flat feet can contribute to knee or back pain.

Tight calves can set you up for plantar fasciitis.

Red Flags: When to Seek Professional Help

You can’t put weight on your foot.

Numbness, tingling, or burning won’t go away.

Signs of infection (redness, swelling, warmth, fever).

Pain that interferes with daily activities.

Visible deformity or major swelling.

The Bottom Line: Appreciating Your Foundation

Your feet are remarkable structures that deserve respect and care. Understanding how they work helps you:

Recognize when professional evaluation is needed.

Make informed decisions about treatment.

Appreciate why specific exercises or therapies are prescribed.

Understand how other body parts (hips, knees, back) affect your feet.

On average, you take about 7,500 steps per day — that’s nearly 3 million steps per year, with each step generating forces up to three times your body weight. When you think about it that way, it’s amazing that foot problems aren’t more common. Taking care of your feet with good shoes, exercise, and early treatment is an investment in your lifelong mobility.

References

Kay RM, Tang CW. Pediatric foot and ankle anatomy. Foot Ankle Clin. 2000;5(1):1–26.

Sarrafian SK. Anatomy of the Foot and Ankle: Descriptive, Topographic, Functional. 3rd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011.

Michelson JD. Commonly injured ankle ligaments: Anatomy and biomechanics. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11(3):547–552.

Bojsen-Møller F, Magnusson SP. Muscle function around the ankle joint. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25 Suppl 4:1–60.

American Podiatric Medical Association. Foot anatomy overview. APMA.org.