Hallux Rigidus (Big Toe Arthritis): What It Is and How to Treat It

If your big toe feels stiff, sore, and hard to bend when you walk, you might be dealing with hallux rigidus — arthritis of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint. This condition can limit daily walking, sports, and even shoe choice. The encouraging news is that we have both non-surgical and advanced surgical options, including modern minimally invasive techniques that were not widely available even a decade ago.

What Is Hallux Rigidus?

Hallux rigidus is the most common arthritic condition in the foot, affecting about 2.5% of people over age 50¹. The term literally means “stiff toe” in Latin, and refers to degenerative arthritis of the big toe joint. Over time, the smooth cartilage lining the joint wears away, leading to stiffness, pain, and bony overgrowths (spurs). Unlike a bunion, which pushes the toe sideways, hallux rigidus causes the joint to lock up and lose motion.

Research shows that among adults aged 50 and older with foot arthritis (affecting ~17% of this population), approximately 25% have radiographic arthritis of the first MTP joint².

👣 Curious how arthritis differs from bunions? Read our guide on bunions in 2025.

Symptoms to Watch For

Pain and stiffness at the base of the big toe

Pain worse when pushing off (stairs, running, hills)

A bump on top of the joint (dorsal spur)

Limited upward motion (dorsiflexion)

Difficulty with low toe-box shoes

What Causes It?

The cause is often multifactorial. Multiple authors have noted associations with trauma, iatrogenic causes, and family history. Women and those with bilateral involvement are more frequently affected³.

Genetics: Flat or elevated first metatarsal structure (metatarsus primus elevatus) can overload the joint

Injury: Turf toe or repeated trauma can accelerate arthritis

Overuse: Common in athletes and dancers

Inflammatory arthritis: Conditions like rheumatoid arthritis may mimic or worsen the process

Diagnosing Hallux Rigidus

Physical Exam:

Range of motion testing, especially dorsiflexion

Palpation for dorsal osteophytes

Assessment of joint line tenderness

Imaging:

X-rays: Weightbearing AP, lateral, oblique to evaluate joint space, spurs, sesamoid changes

CT: Detailed 3D bone evaluation for surgical planning

MRI: Identifies focal cartilage loss or early arthritis

Coughlin–Shurnas Classification (widely cited, endorsed in ACFAS consensus⁴):

Grade 1: Mild stiffness, minimal radiographic changes

Grade 2: Moderate stiffness, dorsal spurring, joint space narrowing

Grade 3: Severe stiffness, large spurs, marked joint narrowing

Grade 4: End-stage arthritis, near-total motion loss

⚡ Forefoot pain isn’t always arthritis. Learn how sesamoiditis can mimic hallux rigidus.

Treatment Options

Conservative Care

Up to 55% of patients in early stages improve with nonoperative care⁵.

Shoes: Stiff-soled, rocker-bottom shoes (Hoka Bondi, Brooks Ghost Max) reduce painful motion

Orthotics:

Custom foot orthoses to offload the joint

Carbon fiber Morton’s extension — a rigid plate under the big toe that blocks painful dorsiflexion while still fitting into normal shoes

Other measures:

Activity modification (limiting barefoot/high-impact activity during flares)

Short courses of NSAIDs

Corticosteroid injections (variable relief, not long-term)

Surgical Options

Choice depends on severity, activity goals, and arthritis grade.

1. Cheilectomy (Spur Removal and Joint Cleanup)

Removes dorsal spurs and smooths cartilage

Best for mild to moderate arthritis

Preserves motion and allows sports return

Modern option:

Minimally Invasive Cheilectomy (Stryker system): 3–5 mm portals, fluoroscopic guidance, high-speed burr. Benefits include reduced soft tissue disruption, smaller scars, faster swelling resolution (average 5 weeks), and high satisfaction rates⁶.

2. Osteotomy

Bone cut to realign or shorten metatarsal

Indicated in patients with structural overload

Often paired with cheilectomy

3. Cartilage Procedures

Microfracture or cartilage grafting for focal lesions

Limited long-term evidence in the first MTP joint

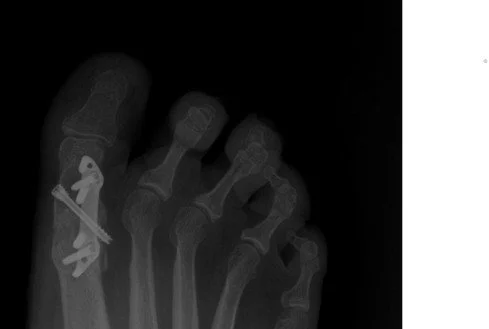

4. Arthrodesis (Fusion)

Gold standard for advanced arthritis (AOFAS/ACFAS consensus)

95% union rates, durable pain relief beyond 10 years⁷

Eliminates painful motion but preserves functional gait

Modern options:

MIS Fusion (Stryker platform): Keyhole access, less dissection, fluoroscopic control

Treace First MTP Fusion System: Low-profile contoured plate with crossing screws, designed for anatomic alignment and earlier weightbearing

5. Arthroplasty (Joint Replacement/Interpositional)

Motion-preserving alternative

Silicone/metallic implants = variable long-term survival

Interpositional arthroplasty (biologic spacers) for select patients

Less common today due to reliability of fusion

| Procedure | Best For | Pros | Cons | Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheilectomy (Open or MIS) | Mild–moderate arthritis | Preserves motion; MIS = smaller scar, less swelling | May fail in advanced disease | Return in 6–8 weeks |

| Osteotomy | Structural overload cases | Corrects mechanics; may delay arthritis | Technically demanding; limited indications | Boot 4–6 weeks |

| Fusion (Arthrodesis) | Severe arthritis | Gold standard; >95% union; Treace = early weightbearing | Loss of motion; no high heels | Boot 6–8 weeks |

| Arthroplasty | Select motion-seeking patients | Preserves motion | Higher revision rates; less predictable | Variable |

Recovery Timelines

MIS Cheilectomy: Walking within days, activity 6–8 weeks

Open Cheilectomy: Similar timeline, more swelling/bruising

MIS or Treace Fusion: Protected WB ~6 weeks, excellent durability

Replacement: Similar early recovery, but higher revision risk

Prevention and Long-Term Outlook

Choose stiff-soled shoes and wide toe boxes early

Address injuries promptly

Do not ignore swelling or early spurs

Early intervention = more surgical options beyond fusion

With proper care — conservative or surgical — most patients return to daily activity with significant pain reduction and functional improvement.

❓ Frequently Asked Questions

Is hallux rigidus the same as a bunion?

No. A bunion drifts sideways, while hallux rigidus causes stiff, arthritic loss of motion.

Can I still run after fusion?

Yes. Most patients run, hike, and cycle pain-free after fusion, though high-heel use is limited.

Is MIS fusion as durable as open fusion?

Early results are promising, but ACFAS still considers open fusion the benchmark until more long-term data exists.

Do all cases need surgery?

No. Many patients do well for years with shoe changes, orthotics, and Morton’s extensions.

👣 Feet Made Simple Resource Box

- Brooks Ghost Max 3 – rocker sole shoe for forefoot arthritis relief

- Hoka Bondi 9 – cushioned stiff-soled shoe to reduce big toe stress

- Topo Ultraventure 4 – wide toe box for bunion and hallux rigidus comfort

- Carbon Fiber Morton’s Extension – limits painful big toe motion while walking

References

Coughlin MJ, Shurnas PS. Hallux rigidus: demographics, etiology, and radiographic assessment. Foot Ankle Int. 2003;24(10):731-743.

Roddy E, Thomas MJ, Marshall M, et al. The population prevalence of symptomatic radiographic foot osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2015;67(9):1312-1319.

ACFAS Clinical Consensus Statement: Diagnosis and treatment of first MTP disorders. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2015;54(6):103-115.

Easley ME, Trnka HJ. Current concepts review: hallux rigidus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(5):991-1002.

Grady JF, Axe TM, Zager EJ, Sheldon LA. A retrospective analysis of 772 patients with hallux rigidus. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2002;92(2):102-108.

Waizy H, et al. Minimally invasive cheilectomy for hallux rigidus: short-term outcomes. Foot Ankle Surg. 2017;23(2):122-126.

Bussewitz BW, Hyer CF. Early weightbearing following first MTP fusion using locking plate fixation. Foot Ankle Spec. 2015;8(1):28-33.

Roukis TS. Outcomes of metallic hemiarthroplasty for hallux rigidus. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50(6):707-713.